Are professors rich?

- Mohit Verma

- May 15, 2019

- 3 min read

So, how much do you earn?

This question is more taboo in the American/Canadian culture than it is in the Indian culture. Thus, although I do not encounter it often, listening to NPR's Hidden Brain podcast “Why no one feels rich” made me think about it. I started wondering about how the salaries of professors compared to other professionals. Given that we just survived the tax season (both in America and Canada) in the month of April, I figured income was a timely topic for this month’s blog post.

Generally, academics are underpaid at all stages of their career (when compared to an equivalent position in the industry): whether you are a graduate student, postdoctoral fellow, or faculty. For most of us, independence is worth it.

Salaries of professors are publicly available

Public institutions (like my own) in the United States release the salaries of their non-student employees on an annual basis. In Canada, the provincial governments require disclosure of employees earning over $100,000 (higher in some provinces) at universities. So, if you like you can look up most professors’ salaries. For example, you can find mine and that of my colleagues’ available here.

Locally, professors earn more than average

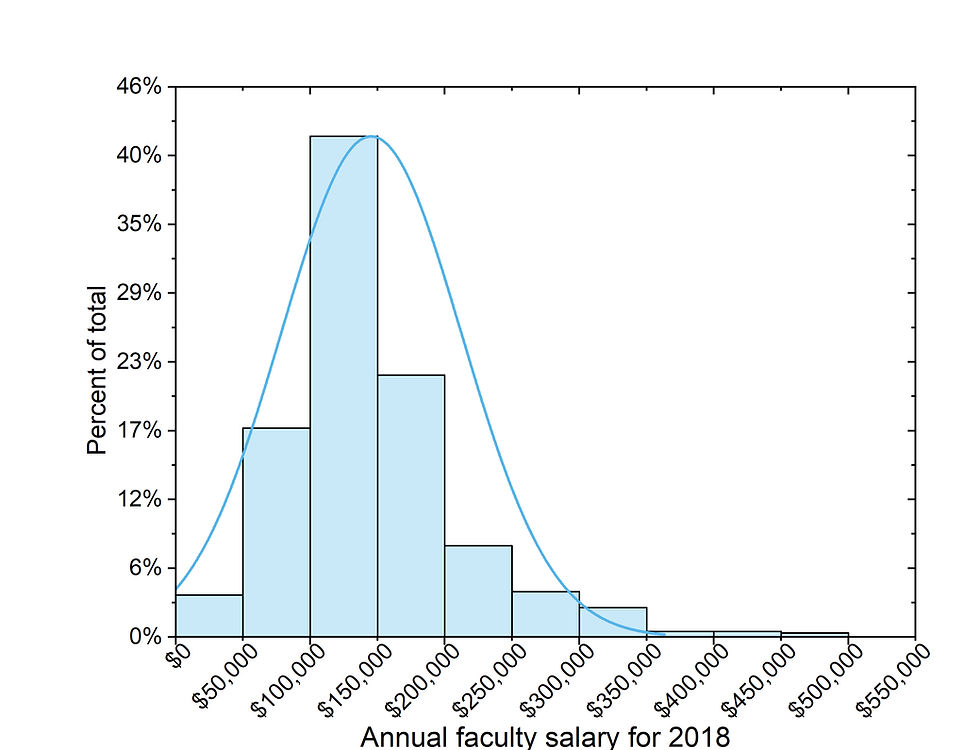

Since the salary data are publicly available, I scraped the information for my institution to generate Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows that most professors earn in the range of $100-150k annually. Note that these numbers include faculty at all ranks (Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Full Professor). Compared to other professionals (administrative and management), the mean value of faculty is higher (Figure 2), but a large fraction of management professionals can lie outside the distribution. In fact, in order to make the plot legible, one person’s salary (over $4 million) had to be excluded from the data. Overall though, the salaries of assistant professors are comparable to the report provided by Glassdoor for the national average of $80,667. Some regions such as the east and west coast will have a slight premium to account for the cost of living.

Compared to other doctors, professors earn way less

Professors and physicians both have the title of “Dr.” Becoming a professor requires a similar training in terms of obtaining a Ph.D. (vs. M.D.) and postdoctoral experience (vs. residency). Yet, if you compare the salaries of a starting professor (assistant professor) to a starting primary care physician, professors earn less than half on average nationally. ($80,677 for assistant professor versus $201,860 for physicians). (Physicians will generally have a much higher debt from medical school to pay off though and thus can take years to catch up in net worth).

Another career route for postdoctoral fellows is to pursue jobs in industry. Although I could not find a reliable way of searching for salaries in the private sector, it is understood that salaries in industry can be 1.5 to 2x higher in industry (see another great blog post detailing experience in industry vs. academia here). If you start comparing hourly wages, these differences can get magnified. While industries generally have fixed (and rigid) working hours, professors have complete freedom (and flexibility). This freedom generally leads faculty to work much longer hours (50 to 60 hours per week) to achieve the required productivity to be successful.

It's not all about money

If you listen to the podcast from the intro of this article, it concludes that feeling rich is all about comparisons. One person's “rich” might be another person's “getting by.” We can use social comparisons for our benefit: by comparing to those earning less, we can feel grateful for what we have and express our generosity towards others; by comparing to those earning more, we can motivate ourselves to move up the income ladder.

Personally, I feel comfortable with my finances. In the end, to me, the independence of my job is especially important. As long as there's enough money for living expenses and fun trips, I am happy!

Comments